25 incredible facts about the Himalayas that will astonish you

At a dizzying 29,032 feet (8,849m) above sea level, Mount Everest is the highest mountain on Earth. But Everest is not its only name. Straddling the border between Nepal and Tibet, the mountain is known as Sagarmatha in Sanskrit, meaning “peak of heaven”, and Chomolungma in Tibetan, meaning “goddess of the valley”. It gained the name Everest in 1865 after the British surveyor general of India, Sir George Everest.

Kanchenjunga is the second-highest Himalayan peak and the third-highest on Earth at an eye-watering 28,169 feet (8,586m) tall. It’s located in the eastern part of the mountain range on the Nepal-India border. Although shorter than Everest, it’s considered a more treacherous climb since less is known about it – just around 20-25 people attempt to summit each year compared to the 300-350 that climb Everest.

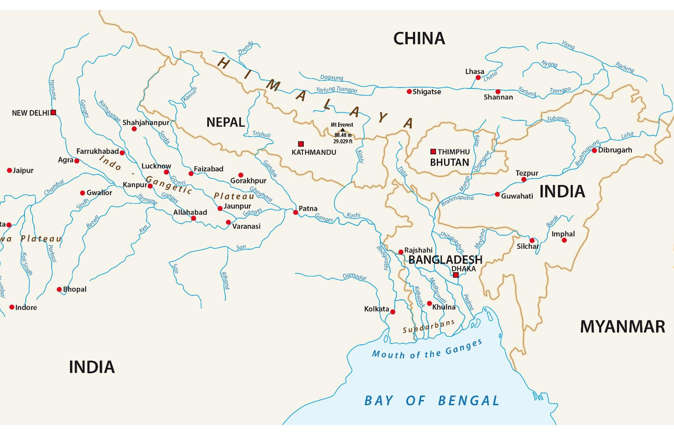

The Himalayas, along with the Hindu Kush and Karakoram mountain ranges, hold the third-largest deposit of ice and snow on the planet. These gargantuan glaciers feed nearby rivers including the Indus, Ganges (pictured) and Brahmaputra which provide freshwater supply to more than 750 million people. However, they’re threatened by climate change, which is speeding up the rate at which they’re melting (as we’ll explore in more detail later).

Until recently, it was thought that the highest mountains of the Tibetan plateau were not inhabited until around 2,500. Yet recent analysis of footprints on the site of Chusang (pictured), 14,100 feet (4,200m) above sea level, has found that the earliest permanent residents have lived in this high-elevation region since between 7,400 and 12,600 years ago.

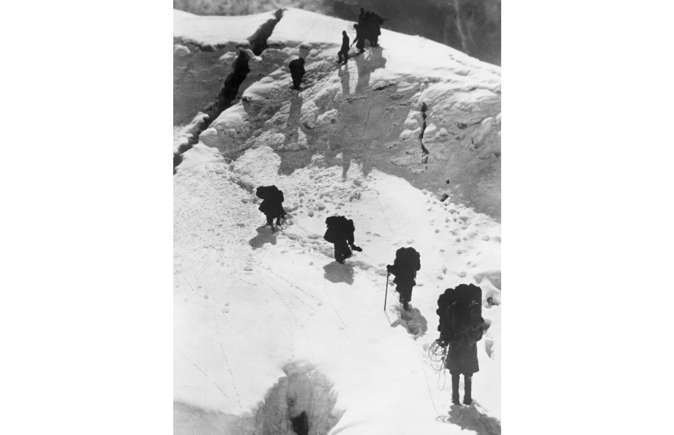

With its remote location, dizzying altitude and almost completely inhospitable climate, Mount Everest has long represented the ultimate challenge to mountaineers. The earliest major attempt to scale the peak was made in 1921, by a group of British army officers, explorers and surveyors under the Mount Everest Committee. But, poorly equipped to deal with the altitude, one member of the group died of heart failure on the approach and the group turned back. Pictured are members of the British expedition in 1936, which was forced to retreat due to bad weather.

By 1933, several further unsuccessful attempts had been made to climb Everest. But two Scottish pilots, Lieutenant David McIntyre and Sir Douglas Douglas-Hamilton, made history on 3 April that year when they were the first men to fly over the mystical mountain. Flying higher than anyone had before, the two men captured important footage which was later examined by Michael Ward, mountaineer and doctor on the successful 1953 expedition.

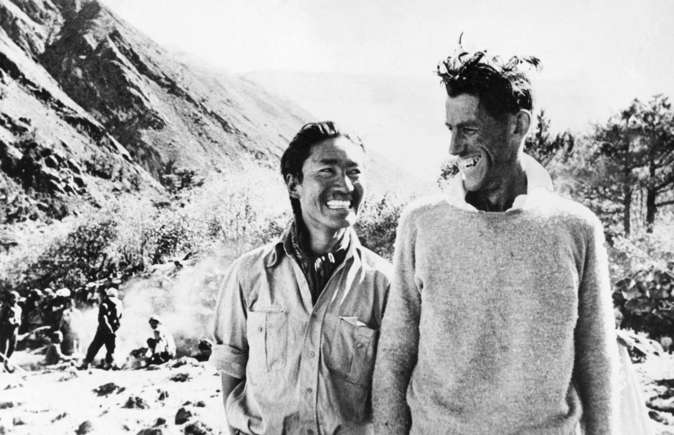

On 29 May 1953, Sir Edmund Hillary, a New Zealand mountaineer, and Tenzing Norgay, a Nepali Sherpa, became the first explorers to reach Everest’s storied summit. The pair were part of a British expedition sponsored by the Royal Geographical Society. Two members of their group, Charles Evans and Tom Bourdillon, had made it within 300 feet (91m) of the summit a couple of days prior but had had to turn back because one of their oxygen tanks stopped working. The news of Hillary and Norgay’s achievement reverberated around the world on 2 June, the day of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation.

Following the successful ascent by the British team, the Swiss were the next to reach the summit of Everest on 23 May 1956. Then on 1 May 1963, James W. Whittaker and Nawang Gombu Sherpa (the nephew of Tenzing Norgay) reached the top as part of an American team (pictured). As well as scaling the peak, the purpose of the expedition was to research how climbers’ bodies responded to such high altitude and having a limited supply of oxygen. In 1965, India became the fourth country to reach the top, putting nine men on the summit of Everest.

Not content with the challenge of simply climbing the mountain, in 1987 Diana Penny-Sherpani created the first Everest Marathon. Despite concerns voiced by the medical community, the event was a success, with 45 athletes from five countries running between Gorak Shep at 17,100 feet (5,212m) elevation and Namche Bazaar at 11,300 feet (3,444m) elevation. The biennial event holds a Guinness World Record for the highest marathon and you can still run it today.

Nowadays, hundreds of people climb Everest each year. But they wouldn’t be able to make it without Sherpas. The name actually applies to a Tibetan indigenous group who live in the Himalayas, but since many Sherpas work as mountain guides, the term has become synonymous with this role. Sherpas are generally better at coping with high altitude than foreign explorers, since they’ve adapted to living in these conditions. They are the backbone of Everest expeditions, showing climbers the safest routes and carrying supplies including extra oxygen, food and water up the mountain.

As well as ensuring mountaineering expeditions run smoothly, Sherpas clear up rubbish left on the mountain afterwards – which can be a huge undertaking. In Tibetan, Everest is known as Chomolungma meaning goddess mother of the world, and the summit is believed to house the Buddhist goddess Miyolangsangma. In recent years, Sherpas have voiced concerns about the sheer number of climbers that scale Everest each year, which has increased the demands heaped on them.

The most treacherous part of the route up Everest is the Khumbu icefall, a steep stretch of the mountain at the head of the Khumbu glacier where avalanches are common. The route is usually secured with ropes and ladders by Sherpas each year. But in April 2014, tragedy struck when 16 Sherpas were killed while preparing the icefall for climbers, after a 7.9 magnitude earthquake led to a deadly avalanche. The event prompted calls for greater rights for Sherpas, who represent one-third of deaths on Everest.

The Himalayas are one of the most seismically active places on the planet, resting on the boundary between the Indo-Australian tectonic plate and the Eurasian plate. But earthquakes aren’t that common here, which made the events of 2015 all the more shocking. On 25 April, the region – along with most of east and central Nepal, and parts of India, Tibet, Bangladesh and Bhutan – was hit by a 7.8 magnitude earthquake. It killed 9,000 people, including at least 19 climbers at Everest after triggering an avalanche on the mountain.

The 2,100-mile (3,440km)-long border between China and India which rests in the Himalayas has been the subject of an ongoing dispute. Since the 1950s, the two countries have fought over where the boundary should lie, with a war breaking out in 1952. Despite an agreement in 1996, which forbade use of explosives and firearms at the boundary, tensions reignited in January 2020 and a fatal clash took place in the Galwan Valley that June. A “minor face-off” occurred in January 2021, according to the Indian Army, although officials from both sides gave away few details about it.

At 22,943 feet (6,993m) tall, it’s not up there with the Himalayas’ big hitters, but Machhapuchhare could be its most elusive peak. Located in north-central Nepal, the stunning, fishtail-shaped mountain has never been summited. That’s due to British army officer Jimmy Roberts, who attempted an expedition up Machhapuchhare in 1957, but had to turn back due to bad weather. Bizarrely, Roberts made the request to ban all climbing on the mountain and the Nepali government obliged. It’s also regarded as sacred by the Gurung people who live in the village of Chomrong nearby.

The Himalayas’ enormous glaciers have long been prone to flash flooding, avalanches and landslides. Yet these events could become more frequent and more deadly due to climate change, which is accelerating the rate at which glaciers are melting. In February 2021, a glacier in Uttarakhand, on the southern slopes of the Indian Himalayas, detached, spurring a lethal flash flood which killed more than 70 people.

Flash flooding isn’t the only issue affecting the region. Ladakh, in the Indian Himalayas, is one of the driest places in the world, and has experienced particularly acute water shortages in April and May during recent years. In an attempt to solve the problem, scientists have created a number of artificial glaciers known as stupas, which store and release water to be used by nearby villages. They were invented by Indian engineer Sonam Wangchuk in 2013, and the project is being developed by researchers from the University of Aberdeen.

In May 2021, a Hong Kong teacher became the fastest woman ever to climb Everest – and she beat the previous record by more than 13 hours. Tsang Yin-hung traveled the distance from base camp to the summit in just 25 hours and 50 minutes, only stopping twice along the way to change clothes. She wasn’t the only record-breaker in the 2021 climbing season: 75-year-old lawyer Arthur Muir became the oldest person to scale the peak, while Nepali Sherpa Kami Rita broke his own record for the most summits, completing his 25th climb.

Despite the fact the first American team reached the summit of Everest in 1963, it was more than 40 years before the first Black climber achieved the accolade. This reflects a broader trend of a lack of diversity in mountaineering – although an all-Black team has recently changed that. In 2022, the Full Circle expedition saw a team of nine climbers, led by mountaineer Phil Henderson, summit the legendary peak. It’s hoped that the expedition will encourage more Black Americans to join the outdoor movement.

Unfortunately, the increased popularity of Everest expeditions has led to overcrowding on the summit. Queues are normal in climbing season, when weather conditions often mean there’s only a short window in which the summit can be reached, but these so-called traffic jams can also be worsened by inexperienced climbers holding up the line. Overcrowding can be extremely dangerous and many Sherpas have called for greater restrictions on tour operators, and a reduction in the number of climbers, to make it safer.

In June 2022, Nepal announced it would be moving Everest’s base camp to a lower-elevation location, as the current area is being destabilised by meltwater. The Khumbu glacier, on which the camp is located, is melting at a faster rate due to climate change, leading to crevasses opening up which are making the terrain unstable and unsafe. The landmark move will see the camp transferred from an elevation of 17,598 feet (5,364m) to an altitude around 656 feet to 1,312 feet (200-400m) lower, according to government officials.

With their legendary, time-honored beauty, the Himalayas grace the wish lists of travelers all over the world. But climate change and tourism represent two of the biggest challenges on the horizon. A report published in 2019 highlighted the fact that the Himalayas are warming faster than the rest of the world, spurring the retreat of glaciers, melting of permafrost and more unpredictable weather conditions in future. Ensuring the safety of climbers and Sherpas on Everest – which may mean enforcing firmer restrictions on tour operators – is another issue that should be at the forefront.

'Wonderful World' 카테고리의 다른 글

| "살면서 처음 본다" 스님도 깜짝…영덕 사찰서 발견된 이 생명체 (0) | 2024.04.19 |

|---|---|

| "살면서 처음 본다"···경북 영덕 사찰에 등장한 '이 동물' 정체는 (0) | 2024.04.18 |

| World’s most incredible sights (0) | 2024.04.18 |

| 황산[黃山]의 비경 (0) | 2024.04.16 |

| 황산[黃山], 중국에서 가장 아름다운 산 (0) | 2024.04.16 |